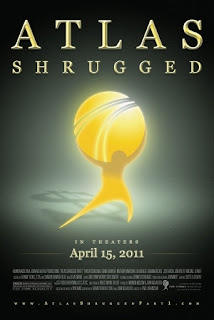

One of the hallmarks of the conservative movement is its hypocrisy: They preach abstinence and have affairs. They run anti-gay campaigns and then get caught in toilets trying to pick up men. But, in conservative circles, they are drooling over the release of the first part of the film version of Atlas Shrugged. Is this hypocrisy or a harbinger of change?

The trailer premiered at the CPAC conference. And conservative web sites have been buzzing with anticipation. What they forget, or ignore, is the utterly contemptible way that the conservatives, especially the pencil-fellator, William F. Buckley, treated Rand. Conservatives despised Rand and she returned the sentiments.

Buckley began the assault on Rand with the publications of a hatchet piece written by Whittaker Chambers in Buckley's National Review. Chambers was one of those Right-wingers who had converted from communism to Christianity and thought this represented a significant evolution. In a sense it is. What communist leaders do to the people as a whole, Catholic priests tend to only do to altar boys.

The Chambers’ review of Atlas Shrugged is no review; it is merely a running series of insults, insinuations and distortions. You learn damn near nothing about the book but you do learn what upsets Chambers the most. He whines that Rand’s book “begins by rejecting God, religion, original sin, etc. etc.” He says the vision of Atlas is “a godless world” and that men, under Rand’s view, seek happiness in this life, something that horrifies Chambers. Because Rand was interested in the world in which we actually live, and not in one that Christian mystics, hysterical saints, and sequestered theologians invent, she is an evil materialist and we all know what that means: “From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding: ‘To a gas chamber—go!’”

One must consider how intentionally insulting that remark actually was. Buckley and his fellow Catholics, steeped in anti-Semitic traditional thinking, knew that Rand was Jewish. Buckley’s own father was a rabid Jew-hater and, according to Washington Monthly, “several of his siblings once burned a cross on the lawn of a Jewish resort.” While the same publication says Buckley was free of anti-Semitism, his magazine, National Review, attracted numerous writers whose anti-Semitism, evolved from latent to blatant. Joseph Sobran, who was at National Review for 21 years, 18 of them as a senior editor, quipped to an audience of Holocaust-deniers that an anti-Semite is not a man who hates Jews, but “a man who is hated by Jews.”

Sobran, in 2005 referred to Jews, as “the Tribe” and defined them as those Jews who support things like “legal abortion, ‘sexual freedom,’ and ‘gay rights.’” That could also define libertarians, I might note. To Sobran the main characteristic of the Tribe is “that they are anti-Christian” and goes so far as to say that Jews adopt their “progressive” views “chiefly because they are repugnant to Christians.” While Sobran seems to indicate he is referring to modern secular Jews that is false. He said “Christians knew from the start how the Tribe felt about them, and nothing has changed since then…” His terminology implies that “the Tribe” is his term for Jews throughout history, instead of about one group of Jews today. Sobran goes to great length to outline historical anti-Jewish views that, he thinks, proves that Jews have low ethics.

While Bill Buckley is supposedly held free of anti-Semitism, he did more than tolerate it. He seemed to not notice it until it became blatant. He eventually realized he had to cut Sobran loose. But Sobran is alleged to have said that he and Buckley patched things up, in spite of Sobran’s anti-Semitism becoming more and more obvious as he got older. Buckley found anti-Semites inconvenient, but he didn’t seem particularly troubled by them. If anything, he found them more eccentric than repulsive. So he was more than willing to tolerate such eccentricities.

For Buckley, accusing a Jewish woman, whose family was in the middle of the Nazi war, of commanding people to go to the gas chambers was something that could be excused, if not openly praised. This comparison was meant to be vicious. Given that, at the time, Rand didn’t know what had happened to her own relatives during the war this has to be doubly insulting. It is as if Buckley and friends were baiting her with the possibility of her own dead family to force her to reply to Buckley’s incessant demands that she notice him. It was years later that Rand learned that both her mother and her father, along with a sister, died because of the war.

What actual aspects of the novel that Chambers does reference he gets wrong. For instance, he misspells the names of characters and claims that all the characters are “either all good or all bad,” which is false. While Rand had villains and heroes, she also wrote of men and women of mixed-premises who were somewhere in-between. Atlas Shrugged has many such individuals. Chambers should have known that had he actually read the book. However, he complained about the length of the book and only did the review because he was pushed to do it. Like Buckley himself, there is no reason to suppose he read the full book before commenting about it. Chambers knew enough to attack it and he knew the reason he hated it, it wasn’t a religious tract linking freedom to theology.

This is what Rand disliked about National Review. While many think that the attempt to link religion with conservatism began with the Moral Majority, Rand was already attacking that link in the early 60s. She wrote Barry Goldwater about this saying that Buckley’s publication was trying “to tie Conservatism to religion, and thus to take over the American Conservatives.” She says this attempt to merge religion into the conservative movement “began after World War II” and she equated this movement most particularly with Buckley and his publication. The arrival of the Moral Majority later was merely a cruder form of Buckley’s high Catholic traditionalism. They lacked the vocabulary and intellect of the Buckleyites but they made up for that with their fanaticism and extreme commitment.

Rand said that until the mid to late 40s she “don’t not take the issue of religion in politics very seriously, because there was no such threat. The conservatives did not tie their side to God.” She wrote, “There was no serious attempt to proclaim that if you wanted to be conservative of to support capitalism, you had to base your case on faith. Historian Jennifer Burns says that it was Buckley, in his book God and Man at Yale, who “famously recast Rand and Hayek’s secular ‘individualism vs. collectivism’ as an essentially religious struggle, and argued that it replicated on another level, ‘the duel between Christianity and atheism.’” Burns says that it was Buckley who requested Chambers write the article, though Chambers himself “was uninterested” and “reluctant to write such a negative review.”

The Buckley conservatives were fervent anti-Communists but they defined communism by its least important facet, its atheism. Instead of looking at the actual theories that communists believed, and which inspired them to their revolutionary activities, the Buckleyites concentrated on what Communists didn’t believe, at least not the revolutionary communists. Doing so allowed them to reframe the conservative movement as a struggle against atheism. Therefore, it must also be a struggle for religion. Buckley, being a rabid Catholic, attached his anti-Communism to the Papacy—a rather odd thing given that numerous Popes have expressed rather hateful views toward capitalism.

Even odder still is that the first authoritarian communist regimes in the world were not atheistic at all, but Christian.The minister, Thomas Müntzer, once picked by Martin Luther himself, imposed a communist regime on the town of Muhlhausen in 1525. Historian Norman Cohn said that Communists “continue to elaborate, in volume after volume, the cult of Thomas Muntzer which was inaugurated already by Engels." Friedrich Engel’s glorified Müntzer and his theocracy saying that the preacher was a revolutionary who merely used Biblical language to attract the peasants to his campaign.

After this, another attempt at Christian communism was tried in the town of Münster under Bernt Rothmann, a former priest and another friend of Luther’s. This experiment, like the first, ended badly.

Before Lenin established revolutionary communism in Russia, the Christian convert, Hong Xiuguan, established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, which merged communist viewpoints with Christian theology. Mao later honored Hong and his followers as early revolutionaries. At it’s height Hong’s “Heavenly Kingdom” controlled 30 million people and the Kingdom’s attempt to take over all of China, and the resulting chaos and famine, is thought to have lead to the deaths of 20 million people in total.

Even Buckley’s friend, and fellow Catholic, the monarchist Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn noted that “not only does the ethical content of Christianity foster and promote the temptation toward socialism, but also much of Christian imagery and doctrine.” And certainly there is much to say for this theory. Buckley and crew, however, were not interested in history; they were interested in building a new political movement. And it was they who set the grounds for the idea that conservatism is a battle between God and God-deniers. The Religious Right, in the end, is as much Buckley’s child, albeit a bastard child, as it is Falwell’s.

Jennifer Burns writes: “Atlas Shrugged represented a fundamental challenge to the new conservative synthesis, for it argued explicitly that a true morality of capitalism would be diametrically opposed to Christianity.” This meant her “ideas threatened to undermine or redirect the whole conservative venture.” Buckley and National Review had turned the modern conservative movement in America into a religiously based movement. Atlas Shrugged was a best seller, just as Buckley and crew were taking the rudder and steering the direction of conservatism. So Rand was a threat and she had to be stopped. Until his death Buckley never ended his jihad against Rand. He continued to distort her views and smear her every chance he got, while incongruously telling everyone she was insignificant and unimportant.

Given this history there is some amusement to see conservatives latching onto the release of Atlas Shrugged, the film, as some sort of important moment for the conservative movement. Perhaps it is—but in ways that conservatives don’t realize. It is entirely possible that the conservative movement is slowly pulling away from the fusion of Christianity and politics that Buckley helped forge.

The reality is that the fastest growing religious belief in America is atheism. Fully one-fifth, to one-fourth of all young people today are non-believers. Christian fundamentalism, which became the backbone of the modern conservative movement, is in demographic decline. The number of young people in their churches is insufficient to maintain their numbers and fundamentalism is on the cusp of a demographic catastrophe—for them, not for us.

As old conservatives leave this world, for what they assume will be a better one, they are being replaced by conservative youth who are less religious, or even atheists. What this means is that conservatism is going to slowly move away from the culture war that the Religious Right focuses upon. CPAC is one example of that conflict and evolution. Attendance at CPAC is heavily youth-oriented and thus most attendees didn’t mind having a gay group, like GOProud there. Last year when a religious fanatic got up and started damning gay people he was roundly booed by the audience for doing so. So, perhaps, it is no surprise that the Atlas Shrugged movie trailer premiered at CPAC. Just as Atlas Shrugged the novel, came out just as Buckley was forging an alliance between religion and conservatism, Atlas Shrugged, the film, is coming out just at the time that alliance is starting to splinter.

Social conservatism is basically a religious movement. And it is one that is in conflict with both freedom and capitalism. The faith-driven have no problem with such contradictions, they are used to them. But the more rationalistic youth, who are less enamored with faith-based economics, do have problems with these conflicts and are starting to throw out the social conservatism that their religious elders cling to so tenaciously and irrationally. Conservatives face a decision: adapt or die. The old cultural-war is over and they lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment